Workers’ World was launched in 1999, by labour movement activists with a history in the struggle as a project of the Labour Research Service (LRS) and within its strategic plan that highlighted three areas of concern that posed a direct challenge to the labour movement, namely the:

- Loss of leadership to government and big business by the trade unions, especially Cosatu at all levels.

- Severe impact of neo-liberalism on the living standards of working class people and what it represented politically, i.e. an attack on workers’ unity by creating new structural divisions within the labour force of outsourced, labour broker, casual and/or part-time workers.

- Rightward political shift of the labour movement, driven by the leadership to place faith in the ANC government and “social partnership” to deliver better living and working conditions. This had the effect of working class people abandoning their struggle orientation and self-organisation.

Our purpose was to develop an independent workers’ voice and media platform that would contribute towards overcoming and challenging these weaknesses and contradictions, and allow workers to put aside superficial differences and unite in defending and fighting for their own interests. We believe in the power of organised labour, and we were concerned that South African workers – having organised and fought their way into the vanguard of political struggle – were being marginalised. South Africa’s labour movement – one of the most powerful in the world – was at risk of being pushed to the side lines.

This was especially the case as the government increasingly adopted neo-liberal economic policies. South African labour law with its neo-liberal “regulated flexibility” paradigm – but still comparatively progressive when compared to countries like Britain – was increasingly being attacked as “inflexible”, and an anti-union consensus was growing in the mainstream media.

We saw a need to challenge these developments by creating an impartial but working-class biased voice for workers.

The situation today

The period since the end of apartheid has seen growing discontent among the working class and poor in South Africa. Most have seen no substantial improvement to their material circumstances, and yet are confronted with the conspicuous wealth and consumption of both the old, white ruling class, and the new black elite. South Africa remains one of the most unequal societies in the world. Despite positive economic growth rates, the majority of black working class people still live in desperate poverty.

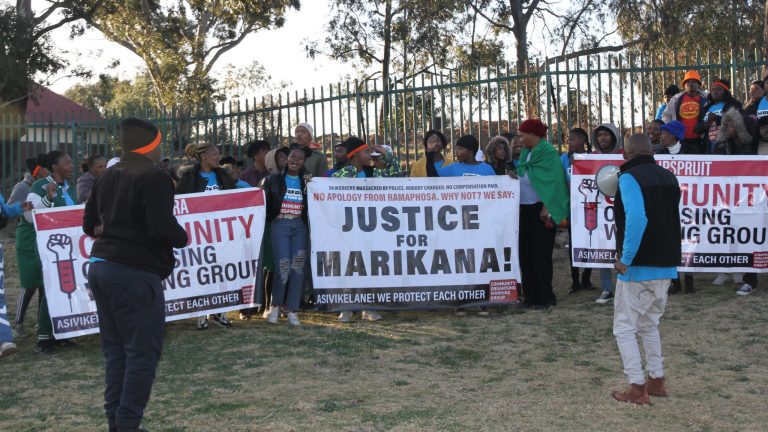

This inequality has led to the rise of new social movements and protests for service delivery. Increasingly, these protests and movements have been met by state violence. However, the depth of the crisis – especially in the labour movement – came to shocking prominence with the Marikana massacre in late 2012. Scores of striking mine workers were shot dead – some executed at point blank range – by the police during a strike. The strike itself was a consequence of divisions in the mining unions, with workers protesting the failure of their unions to represent them adequately. Marikana was followed by a massive wave of workers’ uprisings and protests, not just in mining, but also agriculture, where workers on wine farms set vineyards alight in protest at conditions. The boiling over of frustrations in these two sectors was no accident since they were at the heart of the brutal oppression and exploitation of Apartheid Capitalism and have experienced minimal improvements for workers in the new South Africa.

The consequences of Marikana and the resulting workers’ uprisings have caused pressures and consequently political tensions and divisions within the South African labour movement, especially Cosatu. Cosatu unions are split, broadly, between those that believe they should be directly fighting for the working class and poor, and those that have chosen loyalty to the ANC government and an over-reliance on it to eventually deliver “A Better Life for All”.

An important survey carried out by the labour service organisation, Naledi, shows that ordinary members want their unions to defend their interests robustly, but some in the leadership have acted undemocratically in order to preserve their power and their close links to government. This has led to a deep dysfunction at a time when a powerful and united labour movement is needed more than ever in the face of ongoing economic, social and political crises.

South African workers face a crisis, and the house of labour is divided. With no consistent voice speaking for workers, right wing populists masquerading as left-wingers are filling the vacuum. Stronger organisation and voices from the ground are important, now more than ever, to promote a principled political battle that will ensure a positive outcome of a stronger, united, democratic and independent labour movement.

Our continued relevance

In this context, an independent, reliable voice for workers is needed more than ever. Marikana and the Naledi report highlighted how badly the labour movement has neglected rank and file activists – for instance, only between 5% and 10% of shop stewards have had any significant training over the past decade. This has been borne out by our own direct experience since 2010 when we started embarking on shop steward training in several townships in various parts of the country. This creates a serious issue of capacity, with the movement’s most crucial activists ill-equipped for the tasks at hand. For this reason, we have made a strategic shift over the past two years to reach out to and directly support rank and file activists and shop stewards. In line with this approach we have systematically shifted our resources to be physically located in areas where workers live and work.

We believe that in order to stand a chance of navigating this difficult and contradictory territory, South African labour activists need access to the best possible news, information and campaigning resources. We endeavour, as far as possible, to fill in the media and education gaps left by an official labour movement that is too embedded in its internal crisis to meet the needs of workers.

Our content themes for Media and Education work are:

- Marginalised Workers

- Democracy – Trade Unions and Politics

- Gender and Women’s Oppression

- Discrimination – Racism, xenophobia and homophobia

HIV & AIDS - Occupational Health, Safety and the Environment