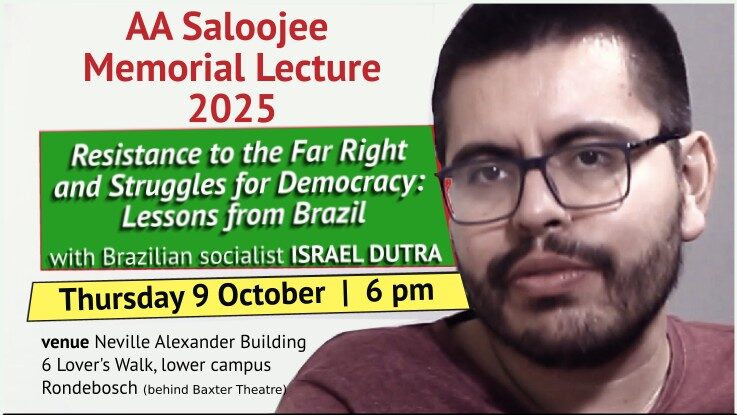

Israel Dutra, AA Saloojee Annual Memorial Lecture, 9 October 2025

Download a copy

1. The Relationship Between South Africa and Brazil – Similarities, Possibilities for Exchange, and Learning

First of all, I would like to thank you for the warm welcome, the exchange, and the opportunity to be here at this conference. I believe this is a historic moment to bring Brazilian civil society closer to South African civil society and its social movements.

South Africa and Brazil share many similar contradictions in the current stage of a crisis-ridden capitalism — increasingly degraded, authoritarian, and driven by its own neocolonial strategy. This is the time to broaden discussions in both our countries, to break the chains of dependency and collectively build our own path forward before it’s too late.

I’m not referring only to the BRICS — which are already a complex reality. I don’t wish to go deep into that topic, as I largely agree with analyses like those of Patrick Bond. What I want to emphasize is that social movements, civil society, democratic organizations, trade unions, and associations in both our countries must make a mutual effort to learn from each other.

The Brazilian people are deeply inspired by the South African struggle for freedom. We share many historical and social experiences. Therefore, we are in a strong position to continue this exchange, and I am sincerely grateful for this invitation — committing myself, after this meeting, to continue fostering the relationship between our peoples.

2. The Urgency of the Moment: Gaza, the Trade War, and COP30

When I speak of urgency, I am not being alarmist. We are facing enormous challenges — some even describe it as the “capitalism of the end of the world.”

We are living through multiple intertwined crises that affect Brazil, Africa, Latin America, and the so-called Global South. I would like to begin by highlighting three of them — pressing and immediate challenges — before addressing the rise of the far right in our country.

First, today we have activists detained from the international flotilla — one of the largest internationalist initiatives in years — organized to break the siege imposed on Gaza. This movement has awakened resistance among tens of millions across the world. There was a general strike in Italy, demonstrations on every continent — the world is watching Gaza, even if most governments do very little.

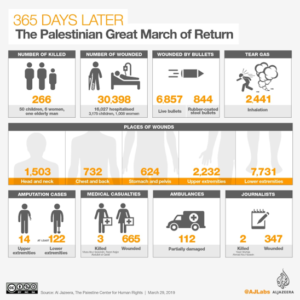

Trump and Netanyahu are the agents of destruction. But Gaza is not only Gaza — it is the laboratory of the far right within this “end-of-the-world capitalism.” We have much to learn from South Africa’s history of apartheid. The genocidal State of Israel imposes a model that merges elements of the Holocaust with apartheid itself. Through white supremacy and ethnic cleansing, this sector of the ruling class seeks a way out of capitalism’s ongoing crisis — a crisis that has only deepened since 2008. Gaza concentrates that strategy, and embodies enormous resistance, as seen in figures like Greta Thunberg.

I was deeply moved when my comrade Martin took me to see the homes and murals in Bo-Kaap painted with the Palestinian flag. This is a struggle that rekindles a sense of solidarity we had not felt for a long time.

Another key aspect is Trump’s imposition of a severe tariff war. Brazil is facing this confrontation — which is not only economic, but also political and structural. Trump and the far right seek to prevent the emergence of other competitive poles such as China and the BRICS. I want to be clear — I do not take China, India, or the BRICS as models, as some intellectuals do. But it is crucial to understand this contradiction, because Trump attacks Brazil and other countries in the interest of broader objectives: the control of mineral resources, rare earths, and lithium — all serving a coalition of three major sectors: mining and oil corporations, Big Tech, and much of the financial world.

You are likely experiencing similar confrontations in your own ways and rhythms. It is urgent — a matter of life and death — to change the dynamics of dependency on imperialism.

Within these global challenges, I must also mention COP-30, which will take place in a few weeks in Belém, at the heart of the Brazilian Amazon. The environmental question is no longer about the future — it defines our present. We are approaching what scientists call the “point of no return.” No previous generation has been so close to reducing the very conditions for life on Earth. Every day brings dozens of new disasters and climate tragedies. And the far right not only refuses to prevent them — through denialism and alliances with predatory sectors, it steps on the accelerator when we urgently need to pull the emergency brake. It’s no coincidence that Trump shouts: “Drill, baby, drill.”

3. To Understand Brazil, One Must See the World – International Elements

Brazil’s current situation is part of a wider international context. Bolsonaro emerged from the same process that gave rise to Trump, Milei, and other far-right figures. Since the 2008 crisis, capitalism has been in open decline.

What has happened since then? A new current has emerged — with neo-fascist traits distinct from historical fascism — that has gained mass influence. This is because capitalism’s structural crisis demands a reconfiguration of class relations, of global hierarchies, and of the organization of labour — especially amid the technological revolution and the rise of artificial intelligence. To preserve itself, the system must attack the workers’ rights won throughout the 20th century, while also deepening the environmental crisis that is eroding the very foundations of “civilization” as we know it.

Brazil is part of this process. Our country has often mirrored global developments. Bolsonaro, Milei, and other far-right extremists are part of the same trend. We could name many others: Erdoğan, Orbán, Modi, Meloni, the far right that attempted a coup last year in South Korea, and Bukele in El Salvador.

In response to capitalism’s crisis, a section of the bourgeoisie — tied to dynamic sectors such as Big Tech — concluded that it could no longer coexist within the post–World War II social pact. Figures like Elon Musk — who defended amnesty for apartheid-era criminals alongside Trump — represent this new alliance, which also includes energy and extractive corporations.

Meanwhile, a segment of the population, disillusioned with supposedly democratic regimes, has channelled its frustration into the far right’s aggressive discourse. We know the far right is not anti-systemic — it is, in fact, the purest expression of the system’s own decay.

Promises made by progressive sectors to improve living conditions were often broken. In places like the UK, labour movements chose to manage a capitalism in crisis, losing their social and electoral bases. Today, Starmer’s government has just 12% approval, and Tony Blair is being considered to help “administer Gaza” with Trump — a grotesque image of how far things have gone.

This pattern repeated in many countries. The incorporation of union and resistance movements into neoliberalism paved the way for a new, more authoritarian bourgeoisie — one that exploits labour and nature more intensely — while large parts of society lose hope and trust. Out of this mix emerged, in a very short time, what some call the neo-fascist current.

Authors like Enzo Traverso, Ugo Palheta, Nancy Fraser, and Achille Mbembe have analyzed this phenomenon. In Brazil, our publisher Movimento recently released a book by Roberto Robaina — a leader of the Socialist Left Movement (MES) — which examines these far-right expressions and neo-fascism in detail.

It is no coincidence that during the recent wave of demonstrations — following the tariff war and attacks on the judiciary — Bolsonaro supporters marched waving U.S. flags. There exists a “neo-fascist international” articulated around the CPAC conferences, which have held at least four global meetings in recent years. The same fake news circulates across social media networks worldwide. The cultural and political environment that produced Bolsonaro is truly international.

4. Brazil: Data, Economy, Politics, Population, and History

Brazil is one of the largest countries in the world — in territory, population, and economy. It is the fifth-largest nation by area, home to diverse ecosystems, biomes, and cultures. Within Brazil, we have major cities such as São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Belo Horizonte, Fortaleza, and Porto Alegre — alongside vast natural reserves like the Pantanal and the Amazon, the largest rainforest on Earth.

With around 213 million inhabitants, we are the seventh most populous country and the tenth-largest economy, representing about 2% of global GDP.

Brazil is ethnically and culturally diverse, with a majority of its population identifying as non-white — about 55% — and with a strong presence of Afro-Brazilians. Our history is marked by the genocide of Indigenous peoples and centuries of enslavement of Africans. Violence from colonization shaped our nation profoundly.

Brazil plays a central role in South America, with strong responsibilities toward its neighbours. Our democracy was built upon the myth of “racial democracy,” which excluded the majority of the population from centres of decision-making.

Our industrialization came late — unlike Europe, it developed mainly in the second half of the 20th century, under a brutal military dictatorship supported by local elites in alliance with U.S. imperialism. The current political cycle began with the fall of that dictatorship, through powerful social and trade union movements that opened the path to free elections in the late 1980s.

This process resembles — though with major differences — what occurred in South Korea, Poland, and even South Africa. It led, years later, to the election of Lula, the Workers’ Party (PT), and movements such as the MST and the CUT, following disastrous neoliberal experiments.

However, the transition from dictatorship to democracy left deep scars — such as the impunity granted to military officials and a democracy heavily limited by economic power. Lula’s first governments brought modest improvements but also made concessions and alliances with elite sectors. This generated discontent and gave rise to new movements and parties like PSOL, of which I am a member, and contributed to growing instability.

In 2013, a year before the World Cup — marked by corruption and excessive spending — people took to the streets demanding more rights in transportation, health, and education. The far right took advantage of this discontent, organizing to depose President Dilma Rousseff through a parliamentary coup that installed her vice, Michel Temer. They then mobilized street demonstrations and digital networks to weaken progressive forces and promote Bolsonaro’s name.

5. The Far Right in Brazil and the Crisis of Liberal Democracy

The far right in Brazil emerged in the wake of the crisis of liberal democracy. Just like Trump’s two victories, Bolsonaro came to power by winning the 2018 presidential election. To understand this process, we can summarize it as follows.

5.a – Bolsonaro as an Expression of Crisis

Bolsonaro came to power as the product of multiple crises — a dependent bourgeoisie, the collapse of the so-called “New Republic,” and the re-emergence of dictatorship-era forces. His government’s economic logic was ultra-liberal, supported by the military and sectors of the working class tied to neo-Pentecostal churches. His goal was to undermine democracy, win re-election, and establish a more authoritarian regime. He openly admired the generals and torturers of the military dictatorship.

5.b – The Bolsonaro Government: Pandemic, Mobilization, and Decline

Bolsonaro’s crisis deepened midterm. Trump’s defeat and the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement shifted global dynamics. But it was the catastrophic handling of the Covid-19 pandemic that destroyed his social support. Nearly one million Brazilians died, while the government deliberately obstructed vaccine access and downplayed the disease’s severity. Public outrage grew. The “Fora Bolsonaro” (Out with Bolsonaro) movement filled the streets even amid the pandemic.

In 2022, Lula narrowly returned to the presidency through a coalition with sections of the bourgeoisie. Yet the far right remained strong and active. Without a congressional majority, Lula has had to negotiate with conservative blocs, adopting very cautious social policies.

5.c – The “Brazilian Capitol” and Lula’s Government

The events of January 8, 2023, mirrored the U.S. Capitol invasion almost exactly. Thousands of Bolsonaro supporters stormed the National Congress, the Supreme Court, and the presidential palace — broadcast live on national television. It crowned a coup plot that, under the false claim of electoral fraud, unleashed violence and chaos.

Over the past two years, Bolsonaro and his allies have sought to destabilize the government. Brazil’s judiciary responded forcefully, uncovering plans by Bolsonaro-aligned army officers to assassinate Lula, the Chief Justice, and other officials. Bolsonaro and 13 others — including generals and his own son — have since been convicted.

5.d – Bolsonaro’s Conviction and Ties to Trump

Bolsonaro’s conviction has accelerated political tensions. The next elections are scheduled for October 2026, and he cannot run. He now manoeuvres in parliament seeking amnesty to avoid prison. Recent mass demonstrations — organized by social movements — have brought hundreds of thousands to the streets in over 100 cities, rejecting amnesty and defending the people’s interests.

Brazil faces a crossroads. Many now question deeper issues — national, energy, and digital sovereignty. Social movements are beginning to go on the offensive, beyond electoral calendars, searching for a democratic, sovereign path of their own.

5.e – The Far Right Across the Continent

Brazil’s struggle will not be decided within its borders. It depends on broader regional and global dynamics. The defeat of Milei in Argentina would be strategic — as popular resistance there grows. Latin America, too, faces a crossroads. Musk and Starlink are eyeing mineral and communication resources. In Ecuador, Indigenous movements are leading a national strike. Chile holds elections at year’s end, Peru’s youth are mobilizing, and Colombia’s President Gustavo Petro has shown great courage — especially in his defence of Palestine at the recent UN Assembly.

We hope to engage more deeply with South African struggles and movements across your continent. The two greatest tasks of our generation are clear: to defeat the far right and to prevent climate catastrophe — to, as Walter Benjamin said, “pull the emergency brake” before the runaway train of capitalism in crisis takes us all into barbarism.

6. Building Actions and Alternatives – Immediate, Strategic, and Programmatic

I want to thank you once again for this opportunity and express my deep admiration for the South African people who defeated apartheid — for your social movements, your universities, and especially for AA Saloojee, whose initiative has made this wonderful exchange possible.

I would like to extend two invitations:

First, that we strengthen our dialogue and coordination between Brazil and South Africa — uniting our struggles against the far right, inspired by the recent example of the flotilla to Gaza, which was seized by the Israeli state and included militants from many countries, among them members of my party, the Socialism and Freedom Party (PSOL).

Second, to move from words to action — to join the effort now underway to convene the First International Anti-Fascist Conference, to be held in Porto Alegre, in March 2026, organized by social movements, trade unions, and parties such as PSOL and PT, and supported by international organizations including comrades from the CADTM [Committee for the Abolition of Illegitimate Debt] and others.