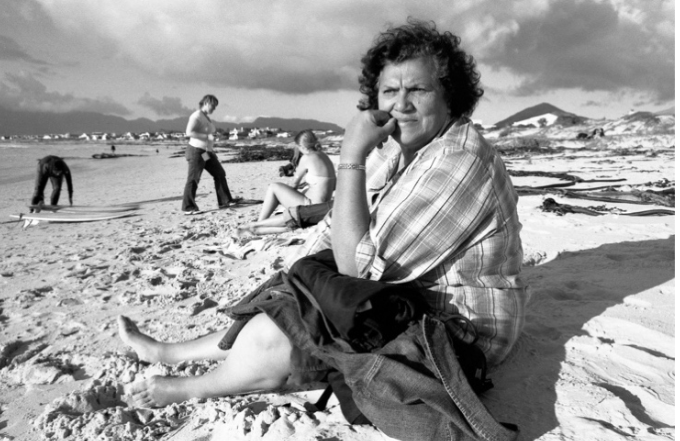

Obituary by Jennifer Fish

Myrtle Witbooi, a pioneering leader of the domestic worker movement died on January 16 in Cape Town at age 75. Under South Africa’s apartheid rule, she began to organize women in the garage of her employer and went on to become president of the first global union led by women. For 52 years she advocated for the rights of domestic workers, upholding her presidency in both South Africa’s national union of domestic workers and the International Domestic Workers Federation throughout her struggle with a rare form of bone cancer.

Ms. Witbooi’s experience as a domestic worker under apartheid guided her life on the front lines of both a national and global movement to history.”recognize and protect women once considered “servants” without rights. She fought for domestic workers’ first legal protections in South Africa’s democracy, which set basic conditions of employment and allowed over 100,000 women to receive maternity and unemployment insurance over the past twenty years. In 2008, her leadership expanded to the global organization of domestic workers, where she guided a campaign for the first international standards of protection for household workers through the International Labour Organization. Her voice appealed to world leaders, as she asked for policy recognition for “those left in the backyards” and the “women who iron your shirts.” In 2011, the United Nations adopted the first international convention for domestic worker rights—a victory that left Ms. Witbooi proclaiming “Today we’ve got our dignity and respect. Slaves no more, but workers just like all of us.”

When asked about her achievements as a global human rights leader, she would most often share her surprise about the course of her life, given her origins under the apartheid system. Born August 31, 1947, in the Moravian mission town of Genadendal, Ms. Witbooi left for work in the city of Cape Town at age 17. She became a live-in domestic worker—one of the most important forms of labor to reinforce apartheid’s interconnected race and gender oppressions. As she cooked, cleaned, and cared for other people’s children and elders, she began to ask why those considered “one in the family” are least paid and universally unprotected. “In South Africa, the law said, ‘if the master speaks, you listen.’ But I went up to the woman I was working for and I said, ‘look at me, I am a woman, just like you.’” In 1971, she spoke publicly about the need for protections such as minimum wages and vacation time by writing to the Cape Town regional Clarion newspaper, which quickly made her a leading voice for domestic worker rights. “Why are we different, why are thereno laws, why are we not seen as people?” The apartheid state deemed her efforts to organize workers illegal. Yet, she gathered women together in discreet locations, building support, writing letters for better working conditions, andencouraging a collective movement of those isolated in “the maid’s quarters” throughout South Africa.

Ms. Witbooi went on to co-found the South African Domestic Workers Union (SADWU) in 1986, the first national organization for women workers in households. She joined the African National Congress resistance movement, working alongside struggle leaders Desmond and Leah Tutu and All an Boesak. During the height of South Africa’s police state in the 1980s, her activism aligned with the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU), bringing the representation of over 40,000 domestic workers into the political struggle to end apartheid. For organizing workers and speaking truth to power, she was sent to prison three times and nearly lost her life to a bomb attack in Cape Town’s Community House. As she fought for women’s and worker’s rights for 27 years under apartheid, she accepted the risks to her own life for the sake of the larger freedom movement. For her, democracy had to be made, struggle by struggle, not won in a single moment. “We wanted freedom, but it was not going to be given to us on a golden platter.”

A fierce grit and unwavering commitment to the freedom struggle anchored Ms.Witbooi’s entire activist life. “Because of my voice, I was determined, and I didn’t let anything stop me.” She spoke out for equality, gender rights, and labor justice, carrying the banner “women won’t be free until domestic workers are free” throughout the streets of South Africa, and later the world. Her children described a certain softness” and diplomatic ease that persistently balanced her intense determination. In her direct work with thousands of domestic orkers, she modeled a practice of speaking from a place of pride and equality, as a means of confronting systems of injustice. “When a domestic worker says, but I am not educated? I said, don’t let education stop you for what you believe in.” A steadfast model of humility, as she realized international recognition, Ms. Witbooi would often recollect “I got my degree in the kitchen.”

South Africa’s 1994 realization of democracy and its ambitious 1996 Constitution made her even more determined to demand domestic worker protections. “We were free in South Africa, but domestic workers were still last on the agenda.” The first labor laws emerged with explicit exclusion of domestic workers—a contradiction Ms. Witbooi utilized to call the new leaders to task. “We challenged our government. We chained ourselves to the gates of Parliament. We locked our Minister up and we put away the key, until they give in.” With these strategies, during her leadership as the President of the South African Domestic Service and Allied Workers Union (SADSAWU), South Africa passed five major labor protections that included domestic workers for the first time. These victories“on paper” gave Ms. Witbooi ground to demand better practices beyond SouthAfrica, claiming “beautiful laws are not enough because there’s a struggle in the world.”

For fifteen years, Ms. Witbooi served as president of both South Africa’s national union and the International Domestic Workers Federation. She became the international voice for domestic workers, traveling to 48 countries to advocate for the protections established in the ILO Convention 189 on Decent Work for Domestic Workers, while overseeing her national union’s daily operations and many requests for mediation. She saw 35 countries ratify this convention and assure national legal protections for workers “in the shadow economy” worldwide. Known widely as a principle-centered, determined, and visionary leader, Ms. Witbooi’s calming force provided an assurance of ease in moments of conflict and a symbol of the ideals at the heart of the wider human rights movement. She balanced spontaneity with careful measure, and good humor with calling those in power to task. The ability to speak from her own experience reflected her most persuasive gifts. She considered the life stories of the domestic workers she met around the world to be her greatest source of inspiration.

Ms. Witbooi’s address to the ILO in 2010 captures her life stance as a champion for human rights and a consistent reminder of the long haul to realize justice, “If anyone would have told me 45 years ago today, that I would be here, I would not have believed them. But I will continue fighting for domestic workers rights every day of my life, as I remember those early days that led me to this particular struggle which has now made its place in world history.”

Ms. Witbooi is survived by three children, Jacqui Michels, Linda (Wayne) Johnson, and Peter Witbooi, along with three grandchildren. She leaves a legacy in both national and international organizations and the tangible legislative victories from her lifetime of activism. In an interview conducted three years ago for her biography, Ms. Witbooi shared wishes for those inspired by her story. “I want you to remember me, unite and organize. I want you to remember, if I can do it, you can do it, and together we can sing, Amandla!”

by Jennifer Fish