by Jeremy Daphne and Lorena Núñez

Six weeks into the now historic Chilean 2019/20 uprising, we expressed the rather daring and euphoric words that ‘’something very different is happening’’ and that ‘’the collective consciousness of the nation has undergone a seismic shift’’ (Workers World Media, December 2019). We also asserted that ‘’running through everything is a deep groundswell – a groundswell of history in the making’’.

A very long and tumultuous year later, the groundswell has become a tidal wave, much to the surprise of many and exceeding all expectations! As it transpired, nothing could stop this groundswell, not Covid, not the lock downs and not even the strenuous resistance and repression by the Piñera government and the broad right.

As a result of the uprising, Chileans voted on the 15th and 16th of May 2021 for a 155-seat constitutional assembly to forge a new constitution, along with electing governors, mayors and councillors across the country – with dramatic outcomes!

A political earthquake

The now often-used description of the electoral outcomes as a ‘political earthquake’ is apt. It constituted a fundamental rejection of the political and business elite, along with other mainstream organisations both to the left and right. It was also a decisive vote against the neoliberal policies and practices triggered by the Pinochet regime fifty years ago.

Importantly, the right-wing coalition fell far short of attaining the one third representation in the constitutional assembly, which would have enabled them to veto decisions. They only obtained 37 seats, or 23% of total representation, with candidates who were heavily funded by business.

The independents obtained 48 seats, constituting almost one third (31%). The leftist parties constituting a grouping called Lista Apruebo Dignidad, which includes the Communist Party and the Frente Amplio, obtained 28 seats. The mainstream opposition parties grouped in the Lista del Apruebo obtained 25 seats. Indigenous peoples were reserved 17 seats. This means the two left coalitions, the independents and the Apruebo Dignidad, will dominate the assembly.

This dramatic trend was also manifested in the elections for governors, mayors and councillors, changing the face of Chile virtually overnight! And this is confirmed by an activist lawyer from central Santiago, who was a key informant for this article, ‘’Everyone is saying that the shift to the left is very clear’’.

Another important feature is the fact that gender parity for the constitutional assembly was achieved by the feminist movement, a first in the world for this provision. As a result many more women than usual ran as candidates for the various positions to be filled in this election. It also resulted in a large proportion of women being elected to the constituent assembly. So much so that some women now have to give seats to men to achieve gender parity!

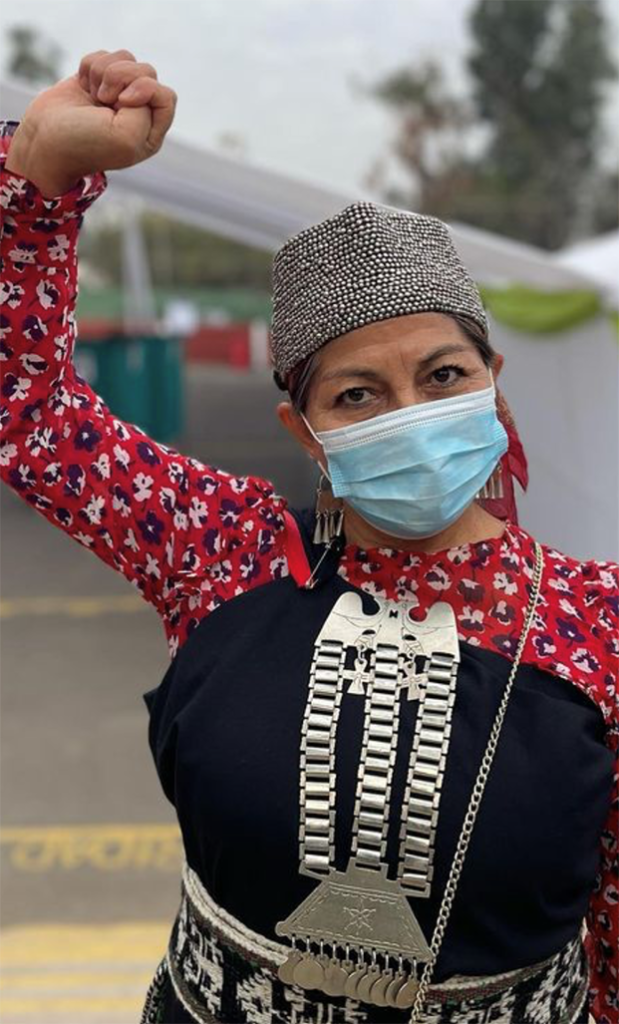

A significant number of representatives to the constitutional assembly have committed themselves to strive for a feminist constitution. This could mean, for example, the inclusion of parity as a constitutional principle to be applied to all the state institutions. This stands to have far-reaching effects in the constitution-making process. In addition, indigenous peoples will now for the first time have a strong voice in writing the country’s new constitution.

Disclosure of personal interests for constitutional assembly members Members of the constitutional assembly will be required to disclose personal interests as a condition of participation in specific debates. In debates regarding the nationalisation of water for example, those who have interests need to abstain themselves from the discussion (access to water, such as rivers, has been privatised in Chile!). It was found that eleven of the elected candidates own access to water rights, with ten being members of political parties (none of them from the left). Much has already been written about this historic development and the focus of this article is on exactly who were the victors, why were they so well supported and what are the implications looking ahead.

A victory for the non-traditional left and anti-neoliberalism

This was a victory for the people that now make up the non-traditional left in Chile, along with the left-orientated political parties. It needs to be said at the outset that this constituency has a number of important characteristics that make this election profoundly important, not only for Chile, but more broadly.

Firstly, neoliberalism was the key issue focussed on across the various groupings and parties, with anti-neoliberal perspectives being clearly expressed. In fact, the battle lines have been drawn around this issue. In addition, a strong feminist perspective prevails. This constituency is also generally young. The average age for the constituent assembly members is 45, for example.

It thus can be said that the election results were a victory for the feminist movement, for anti-neoliberalism and for the youth.

Candidates from this left constituency also campaigned on issues, spoke a language and expressed sentiments that resonated with voters. Candidates were respected for having a record of being on the streets interacting on a continuous basis. This applied both for assembly seats and those for governors, mayors and councillors. Linked to this, people and in particular the youth, did not vote along traditional lines, rather supporting candidates that appealed to their direct interests and their vision of a new society.

Who are the non-traditional left?

What is termed the non-traditional left are the people who stood as independents in the elections, along with their supporters. They consist of a diversity of people from all walks of life who came together as activists in the uprising. Leading up to the elections the independents formed themselves into a grouping, called La Lista del Pueblo. An important layer within this grouping are the radical independents, who spear-headed this initiative.

In addition to professionals now holding seats, such as lawyers and journalists, there is, for example, a woman who drives a school bus and became well known for her role in demonstrations dressed up as a children’s character. She has been outspoken in presenting the reality of people like her who could not afford to go to university. Another example is a man who has been living with leukemia for seven years and who has interacted intensively with the public health care system and the reality of that.

A victory as well for left parties out of the mainstream

In addition to the right, another casualty of the elections were the parties forming the historical political alliance the Nueva Mayoría (previously Concertación de partidos por la Democracia, linked to Michele Bachelet’s last centre-left Government). The notable exception is the Frente Amplio, a coalition of left-orientated parties coming from the student uprisings over the past decade. The other political party on the left that received support is the Chilean Communist Party, which remained steadfastly independent from other parties in events leading up to last week.

In the view of the communist re-elected major of the Recoleta district in Santiago, Daniel Jadue: ‘’the dividing line among the various opposition parties runs along those which clearly reject the neoliberal model and those who support the model’’.

The case of the Valparaiso Region Standing as an independent, Jorge Sharp, the progressive mayor of the Chilean capital Valparaiso, was re-elected. In addition, Rodrigo Mundaca, representing the Modatima formation (Movement in defence of water and land access and the protection of the environment) won the governorship of the Valparaiso Region. An engineer, ecologist and human rights activist, he promotes access to water as a public good and as a basic and essential human right. As newly elected governor of Valparaiso he has already announced he will put a halt to businesses and developments that disregard the protection of the environment, such as luxury hotels adjacent to communities in water scarce areas, threatening their livelihoods and infringing on protected areas. In the view of the activist lawyer from central Santiago, the Frente Amplio and the Communist Party enjoyed support not only for their political stance but also due to fielding young, dynamic candidates who connected to people on the street. Citing the example of the 30-yearold woman (Irací Hassler) from the Chilean communist party who won the mayoral seat for central Santiago, he commented that ‘’She was a member of the cabildo (local assembly) and she was in the street all the time. She was supported not because of the Communist Party but more because she was connected.’’

More significant than Allende’s 1973 victory?

A well-respected, independent Chilean radio journalist Tomas Mosciatti in analysing the outcomes, argues that this is more significant than Salvador Allende’s 1973 electoral victory in a number of respects and that it constitutes a profound challenge to neoliberalism. When Allende took power with a support of 34% of the votes, he could not rewrite the constitution. He initiated his transformation process adhering to the existent set of laws. Chile’s current elections have demonstrated the left have won the democratic right to re-write the ‘rules of the game’, with a country significantly wealthier than what Chile was at the time of Salvador Allende’s government.

The demise of the right?

The vice-like grip of the right-wing, along with the associated Pinochet-era constitution, now finally stands to be broken. The menacing shadow of the right, including the political and business elite, has been present since 1973 and was not removed after Pinochet’s downfall in 1990. This culminated in Sebastian Piñera’s ascendency to power in 2018 and the intensification of the hyper-capitalist agenda and state repression. Fundamental transformation of this model is now very possible, with the right in crisis mode.

However, the question of the demise or otherwise of the right, including their potential to undermine the transformative process, is important. The new constitution, when settled in the assembly, still needs to be voted upon in another referendum, involving a simple majority. The right will still be left with the possibility to call for a rejection of the constitution and play upon the fears of people (for example the use of ‘Chilezuela’ references). While, perhaps arguably, it is unlikely that they will have the power or support to put a halt to these historic changes, this matter will be a factor to take into account in the process going forward.

Re-energising and re-imaging the left

As can be seen, this development has dramatically brought to centre stage a new left formation, constituting what has been termed the ’non-traditional left’ and some established left political parties. Underpinning this left formation are a set of common political perspectives, as described above.

This stands to significantly energise and provide direction for the broad left in Chile, not forgetting the challenges ahead, while it will be the cause for much introspection for some. This includes the trade union movement, whose key representatives in the Unidad Social, a trade union / civil society coalition, were not elected.

There is no doubt that many questions can be raised in this regard, but a tectonic political shift has happened, with the ascendency of a new left vision. The main elements of this vision arguably differ from that of the more traditional left, such as prevailed for the brief and tragic period when Salvador Allende came to power in 1970. Compared to the historical period encompassing the three years Allende’s socialist government was in power, which ended abruptly with the United States supported military coupe, it goes without saying that a different world now prevails in Chile (and beyond).

Finally, this development stands to have impact beyond Chilean borders, with learnings to be gleaned while the process unfolds. It hopefully will also inspire the masses of people and in particular women and youth, within Latin America and beyond.

Lorena Núñez is a Chilean and an Associate Professor based in the Department of Sociology, University of Witwatersrand.

Jeremy Daphne is a former trade unionist now working on a part-time basis for the Bench Marks Foundation on a project supporting mining impacted communities.